|

About This Site : Getting Started | Contact | About This Project | How To | Honors | Credits | Tech Info

How To Make a Site Like This

Overview

Managing the 1704 Website Project

Design and Production

Technology

Managing the 1704 Website Project

Page Contents:

Introduction | Planning and Defining the Website | Building the Website | Publicizing the Website | Evaluating the Website

Introduction

Project management is the glue that makes everything

work together. It's the imposition of order on an otherwise chaotic

mishmash of tasks that must be accomplished. It answers these

questions: What are we doing? Why are we doing it? How are we

going to do it? Who is going to do it? When are we doing it? How

will we know when we've done it? How will we know if it's any

good? On any project, one mind needs to be able to hold everything

and see the big picture. How is that accomplished?

The project manager should have experience managing

large, multi-faceted projects—preferably online projects (websites,

computer-based training, distance learning, etc.). She should

have experience talking in the language of online design and development

so she speaks the same language as the designer and programmer.

She should be familiar with the issues that arise in the area

of website content: finding good writers, choosing between a good

writer and a subject matter expert, the writing and revision process,

the implementation process—getting writing online, reviewed, and

revised. She should understand enough of the technology behind

the website to be able to grasp the development process, especially

when estimating resources—people, time, money. She should be a

good communicator, a consensus-builder, and a cheerleader.

We managed the 1704 website project by dividing it into five phases, developing processes for each phase, and then checking to make sure that those processes were followed.

- Planning and Defining the Website

- Designing the Website

- Building the Website

- Publicizing the Website

- Evaluating the Website

Planning and Defining the Website

If you have written a proposal (see

IMLS Proposal, 154K pdf file) and received grant money for

your project, you have most likely completed some of your project's

planning tasks, at least at a high level. Hopefully, at the very

least, you have determined the goals of the project and some ideas

of how you are going to accomplish those goals in terms of resources,

general timeline, and budget. A key additional task during the

planning stage involves preparation for the design and development,

or building, phase.

This preparation include the following tasks:

- Clarification of audience

- Formulation of detailed objectives and outcomes

- Determination of policies

- Detailed outline of development tasks (including a timeline

and schedule with milestones)

- Outline of content and formulation of a writing and review

process

- Definition of responsibilities based on a compilation of resources

- Development of processes (for example, design and development,

writing, reviewing, revision, getting content online, etc.,

and standardization of those processes in the form of a Standards

Manual or Writing Guidelines (see

Writing Guidelines, 33K html file)

- Formulation of an evaluation process

- Determination of the technology necessary to accomplish the

goals of the project

- A process for keeping track of everything

Often, this phase results in a Project Plan which describes the design, development, and evaluation

activities. Or, if your proposal was detailed enough, you may spend

a planning stage fine-tuning what was in your proposal.

We were fortunate to be granted an NEH Planning Grant which allowed us a six-month planning process. During these six months, we were able to bring many of the players from the different cultures to the museum to meet face-to-face and hammer out key content and design issues. It was during one of these meetings that we realized we needed a tab approach to the multiple perspectives of the site, thus allowing each culture to tell its own story.

Building the Website

In the development phase, the team moves into the actual building of the website. It is helpful if the planning phase includes time to develop a number of processes that occur concurrently during the development phase. These processes include communication among members of the project team; the research, writing, review and revision process for content (both text and illustration) creation; implementation—or, getting the content into the website; and formative evaluation—a process for reviewing the online content and making sure it is correct and "works"—both in terms of its accuracy and its functionality.

Communication

Communication was a challenge: at various points in the four-year-long

project, over 60 people worked part-time on the website, at one

point or another, and most of them were scattered geographically.

Only the project manager and one part-time historian were resident

at the museum. As a result, we held very few in-person meetings.

Most of our communication occurred via phone and email and postings

to a team website (see screen shot of Team website below). The

project manager compiled task lists (see

Scene Schedule, 59K pdf file), (at a later point in time these

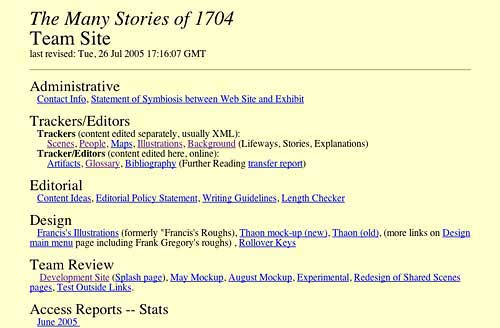

task lists were replaced by Trackers—see screen shot of Scene

Tracker below, and described in greater detail in the Technology

section); monitored progress and issued regular status reports;

and compiled a Standards Manual that recorded decisions made by

the team. Only a few meetings were held at the museum.

Content Development

Content development began in the design phase with a basic categorization

of the major kinds of content that we would include. In our case,

the kinds of content we created were historical scenes written

in a tabbed format, character narratives, labels for artifacts,

a voices & songs section, a glossary, brief descriptions of maps,

essays, timeline content, and a Teachers' Guide. We listed the

content for each category and then developed an outline for the

longer pieces. The tasks of identifying, outlining, and writing

the content occurred simultaneously. For example, while we were

outlining one historical scene, we were busy writing and reviewing

and revising another, and putting yet another online. At the same

time, we were outlining one character narrative, writing and reviewing

and revising another, and putting another online. In some instances,

we had more than one writer working on one category of content

at a time. We used Trackers to keep track of each of the content

areas.

We hired a variety of writers. Our two historians took on a small part of the writing, but their time was mostly allocated to outlining the content and reviewing other writers' work. Several scholars wrote essays for the website. We hired a writer to write many of the character narratives; we also hired three native scholars for to write narratives of Native people's lives. We hired a material culture expert to track down and write labels for artifacts. The project manager wrote some text and served as an overall editor for most of the content. All text content was reviewed extensively for accuracy and writing style.

Review and Revision

We developed a rigorous content review process that spelled out

in great detail the steps writers and reviewers had to follow

to produce a piece of writing, ready to be put online. For example,

for tabbed content, one of our historians filled in a template

for each scene's content, (see

Content Outline Template, 166K pdf file) the content of which

was reviewed by each culture's reviewers. Reviewers were contacted

during the planning phase and sent letters (see

Advisors' Letter, 47K pdf file) explaining how they should

review and give feedback, and how they would be paid. Reviewers

from each culture were told that they had to agree among themselves

on the changes requested, so that the museum was not in the position

of having to mediate among the various voices within each culture.

The historian revised the outline based on the feedback and submitted

the outline to the writer.

The writer did research (if necessary) based

on the outline, then submitted a draft of the various tabbed perspectives

for the historical scene she was writing; at most, there were

six tabs—the introduction tab and a tab for each of the five cultures.

Advisors for each culture, plus a group of scholars, reviewed

the content and submitted revisions. The writer and historian

reviewed the feedback, and the writer—in consultation with the

historian—made the necessary changes. The advisors and scholars

reviewed the revised text. All of this review (including directions

for how to review and give feedback (see

Reviewer Directions, 4K html file) took place on the team

website, with feedback sent to the project manager who distributed

it to the writer and historian. When the content was deemed ready

for implementation, the project manager sent it to the implementor—a

college student who worked at a fairly low rate, compared to the

programmers of the website. Other pieces of content, including

illustrations, were treated in a similar manner. We followed this

iterative process for approximately two years.

Implementation

Once a piece of content was ready to be put online, our historian readied the file to be sent to the implementor by doing the following:

- Checking proper format, including heads and subhead, footnotes, and further reading in the case of essays and character narratives

- Adding glossary term definitions if the writer had not previously done so

- In the case of essays, character narratives and some historic scenes, determining the illustrations that would accompany the piece, their location, their captions, and a link from the caption to an artifact label if the illustration illustrated a website artifact

Once the implementor added the content to the

development site (See the Technology

section of "How To" to learn how we did this.), the historian

and writer reviewed the content and made any necessary changes

before the project manager sent an email to the reviewers to review

the content online. We instructed reviewers to send feedback to

the project manager who, in turn, passed it on to the historian

and writer for revisions if necessary. Final changes to the online

material were made by the historian, the writer, or the implementor.

Standards Manual

A Standards Manual is a written expression of standards that are agreed upon conventions, subject to review, that guide you in developing a website. It should be flexible and serve as a model, or guide, that writers, designers, developers, and programmers can follow in spirit, if not in fact. The content of a Standards Manual should be subject to review and not cast in stone, changing to accommodate new understandings and different project needs. It should be added to, reviewed, evaluated, and changed if necessary, in an ongoing effort to make it current and helpful. The Standards Manual should be a working model and evolving document.

Why is it helpful to have a Standards Manual? Developing and writing down standards does the following:

- Saves us from having to reinvent the wheel each time we add content to the website

- Saves us from having to decide what style and conventions to use, remember them, and undo costly errors that result from misunderstanding, or inaccurately remembering them

- Makes everyone feel a part of the process

- Allows us all to benefit from the combined wisdom of everyone’s experience

- Helps website visitors learn by providing clarity and consistency,

enhancing aesthetics, increasing interactivity and learner control,

making content educationally sound and internally consistent

- Makes the content of a website look like it was written by one person

Our Standards Manual (see

Writing Guidelines, 33K html file) includes the following

sections:

- "How to write" topics for the various types of writing that

appear on the website (for example, tabs, character narratives,

artifact descriptions, rollovers, etc.)

- Using templates

- Writing style: capitalization, spelling, terminology

- MS Word document guide

- XML document guide

Publicizing the Website

Publicity was an important part of our project

plan both because we wanted to make sure that people visited our

website and because one of our grants was a National Leadership

Grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services. We were

charged with the task of disseminating our website as a model

for other institutions. Our detailed publicity plan developed

over time; it began in the planning phase and in the proposals

we wrote, and continued into the design and development phase

in the form of a series of meetings with the marketing committee.

These are the primary activities we set in motion to publicize

the 1704 website. Each activity involved planning, task lists,

the allocation of staff time, possible budget considerations (especially

in terms of the design), development and distribution of postcards

and bookmarks, and an informal assessment of its effectiveness:

- Pre-site: Before the site was launched, we added a "pre-site"

that provided a preview and description of what the site would

be. We linked to this "pre-site" from the museum's existing website.

- Video preview and press release: We developed and disseminated

a four-minute video tape and press release about the website

to key media outlets.

- Promotion at museum events: We advertised the website to over

60,000 people at six different Old Deerfield Craft Fairs, (see Craft Fair website)

sponsored by PVMA.

- Radio and TV: We disseminated promotional materials to radio

and television stations in the weeks leading up the launch.

- Related events in other media: WFCR (PBS affiliate) aired

a raid series "Captive Lands, Captive Hearts," (see

Captive Lands, Captive Hearts) in the week leading up to

the launch; this series has now been incorporated into the website.

Additionally, we sponsored eight performances of the opera,

the Captivation of Eunice, presented during a second commemoration

weekend in Deerfield in July of 2004.

- Bookmarks: We sent out 50,000 bookmark to libraries and school

libraries, state-wide.

- Website announcement postcards: We mailed 14,598 postcards

announcing the website to regional subscribers to Smithsonian

Magazine, and 5,000 post cards to PVMA members and museum mailing

lists. We distributed thousands of postcards at conferences.

- Website "How To" postcards: Because we received a National

Leadership grant, we announced that the technology behind the

website would be free to non-profits by mailing 11,000 postcards

to mailing lists from the New England Museum Association (NEMA),

the American Association of State and Local History (AASLH),

and the American Museum Association (AAM).

- Related exhibit: We attended planning meetings for a joint exhibit

with Historic Deerfield, Inc.

- Town meetings: We attended several town meetings with Historic

Deerfield, Inc. to plan for the 300th anniversary commemorative

events.

- Official launch ceremony: We launched the website to a standing-room-only

crowd during February, 2004, and again in July of 2004. An estimated

3,000 people visited Deerfield at launch.

- Conferences: Staff delivered presentations at conferences.

- Awards: The website won Honorable Mention in the Best Online

Exhibition category at the Museums & the Web Conference in Vancouver,

Canada, in April 2005 (see

Museum & The Web Awards page); it won a National Award

of Merit from AASLH in July of 2005.

- Published articles: The project manager and designer authored

five online articles about the website: for example, Telling

an Old Story in a New Way: Raid on Deerfield in eLearn

Magazine (see

article) and Digital Deerfield 1704: A New Perspective

on the French and Indian War, (see

article) in First Monday, an internet peer-reviewed journal.

- Consultations: The project manager and designer consulted with

other museums/libraries interested in learning more about our

process and website development.

- Presentations at local educational groups: The project manager

and museum staff delivered many workshops about the website

to teachers and students.

Evaluating the Website

As indicated in the evaluation section (see

Evaluation Plan, 46K pdf file) of our proposal, we divided

our evaluation activities into two phases: formative evaluation,

which tells us how we can make the website better based on user

feedback, and summative evaluation, which tells us if the goals

of the website are being met.

How Can We Make the Website

Better?

The formative evaluation answered the question "How can

we make the website look and work better?" and took place at two

key points (pre-public premier: September–February 03; post public

premiere: April 03–March 05). It was primarily qualitative in

nature. We gathered information from observation, interviews,

formal focus groups, and questionnaires (see

Questionnaire, 45K pdf file). This data allowed us to perform

an interface design analysis and, in turn, inform the design and

development of the website so that it was constantly refined and

fine-tuned to better accomplish its objectives. During this phase

we gathered data to answer questions in the following areas: 1)

Use - Who is using the site and why?; 2) Usability - Is the user

interface easy to navigate? Does the user get lost?; 3) Content

and Clarity - Are story lines and terminology clear?; 4) Content

Accuracy - Is the content accurate - determined through advisor

reviews); 5) Effectiveness of Content and Presentation - What

did you learn that you did not already know? How would you improve

the website?.

In all cases, we tried to select a cross-section of users who represented differences in sex, age, geographical location, race, ethnicity, religion, and socio-economic background. For example, college classrooms offer racial, geographic, ethnic, religious and cultural diversity among men and women students. Local libraries and craft fairs provide participants with ethnic, cultural, religious, socio-economic and age differences among men and women.

In April of 2005, we volunteered our website for a "Crit Session" at the Museums & the Web Conference in Vancouver, Canada. Volunteer judges from other museums evaluated the website primarily in terms of ease of use. This feedback from colleagues proved extremely helpful, since these professionals are both exposed to many similar site issues and have given a lot of thought to the same kinds of challenges that we encountered.

Is the Website Meeting

Its Goals?

The project manager began summative evaluation in early spring

of this 2005, with plans to complete it by the end of September,

2005. The evaluation employed both quantitative and qualitative

measures to assess the degree to which the website project achieved

its goals:

- Has the website reached a large and diverse audience?

- Does the website increase users' knowledge of the event?

- Does the website contribute to a greater awareness of, understanding

of, and/or appreciation for, the various perspectives that define

the historical event?

- Is the website successful in helping other institutions develop

their own multi-perspective website?

Quantitative Methodology: We gathered

web server statistics to measure how the site was being used—for

example, the number of "hits" to the website, most frequently

"hit" pages, number of searches and search targets, pages bookmarked,

and length of time on the website. Our programmer developed a

way to track clicks within a Flash presentation in order to evaluate

the extent to which users actually explore multiple perspectives.

We also developed an online survey and an online game (developed

using Flash) that can yield additional information about respondents'

understanding of the multiple perspectives in the website.

Website statistics:

We gathered website statistics (see

Website Stats, 61K pdf file) using the software program

Webtrends. And although you can gain a great deal of detail about

traffic on a site using this tool, so far, we have graphed only

the following information: number of hits, pages views, visitor

sessions, and unique visitors. Hits have relatively little meaning

since a hit is tallied for each file of graphics on each page.

But number of pages viewed has meaning since it is just that—whole

pages being viewed. The pages viewed number is much greater than

visitor session since most visitors view more than one page in

a session. Likewise, there are more visitor sessions than unique

visitors since a given visitor may come to the site a number of

times.

We can see that when the website launched, we

had a great number of page views and visitor sessions; then the

numbers dropped off, decreasing from 56,603 and 15,253 respectively,

to 18,010 and 6,772. The numbers gradually grew from there, tapering

off during the summer when teachers and students are not using

the website. Again, in the fall of '04, the numbers rose sharply,

coinciding with the opening of school, and then fell off again

during the holidays. In 2005, we can see that the numbers took

a huge jump in February and March, most likely due to the increase

in conference activity, continued publicity around the 1704 commemoration

weekend, online articles about the website, and strong continued

use by the educational community.

Preliminary online perspectives tally:

Periodically, we look at the visits to each of the historic scenes

and determine which cultural tabs are visited for each scene.

For example, these are the visitation numbers for the Attack scene

tabs during a four month time period in the spring of 2005: Intro-1,126;

English-290; French-257; Kanienkehaka-251; Wendat-222; Wobanakiak-206.

We are able to say that 166 visitors viewed all five cultural

perspectives. This is somewhat disappointing until one realizes

that these hits include visitors who came to the scene and then

decided they did not want to be there. It is also true that some

people who visited the English tab did not visit the other tabs.

This general pattern of people visiting all the tabs in roughly

the same numbers generally holds true for the historical scenes

that have more than one perspective.

Online survey quantitative data:

All categories were judged on a 7-point scale, with 1 indicating

the positive extreme and 7 indicating the negative extreme; for

example, ease of finding information was judged 2.3 on a 7-point

scale with 1 indicating very easy and 7 indicating very difficult.

Here are results during a four-month timeframe in the spring of

2005:

- Encounter with technical problems - 2.16

- Clarity of writing style - 1.7

- Trust in the information presented - 1.76

- Pleasure in the look and feel of the site - 1.56

- Ease of navigation - 1.8

- Knowledge of the raid before visiting the website - 4.56

- Knowledge of the raid after visiting the website - 2.56

- Awareness of different points of view before visiting the

website - 5.17

- Awareness of different points of view after visiting the website

- 2.65

- Extent to which the website caused respondents to change their

mind about something - 4.78

- Fully 38 % of respondents said that they felt more strongly

about something after visiting the website.

Qualitative Methodology: Qualitative

methods of data collection include online survey questions, questionnaires

filled out by teachers and students, an online game, unsolicited

email feedback, and informal comments at conferences and workshops.

Online survey questions:

These questions indicate that most respondents came to the website

either through school assignments, a research need, or because

someone told them about it. Most problems encountered related

to slow Internet speed or links not working. When asked the single

most important thing that they will remember about the website,

the most common responses indicated the multiple perspectives

(and non-judgmental nature of the site), the informative content

(reasons for the raid, personal stories, struggles, houseplans),

and the graphics and illustrations. There was no aspect of the

website that stood out as being least liked, although respondents

did mention slow speed, links not working, and the need for current

information about Deerfield. Suggestions for making the website

better included adding character narratives, adding a "graphics-lite"

version for people who don't have fast connections, adding a search

function, adding more content, and making maps bigger.

Other questions on the survey yielded information like the following:

When asked what they learned from the website, we can see that some stereotypes were erased, as indicated by this comment:

"I did not know that there were

French people with the Indians in the raid. I had only heard the

'savage' Indians had attacked."

Two additional questions designed to elicit information about respondent's sensitivity to other perspectives yielded these four comments:

"I am more sensitive to others views."

"I feel more strongly about "injustice."

"It is foolish to look at any historical event from one perspective. Great website. We're a Museum Studies class in New Mexico."

"Because I've learned things that I did not know."

Email feedback:

Feedback responses through the website have been many and varied.

They range from genealogists researching their family trees, to

teachers who are using the website in their classrooms, to history

scholars from museums. By and large, all comments have been positive,

even laudatory. It's a good idea to enable visitors to the website

to email someone on the website team; this avenue of informal

feedback is both popular with visitors and unstructured enough

to allow a variety of response—much of it informative and useful,

and it allows the web developers to contact the visitor providing

the feedback and engage in a dialog, if desired.

|

![]()

![]()